Austin, TEXAS/USA - September 11, 2017: Students walking along the South Mall, under oak trees at the University of Texas in Austin (Shuttershock)

Even with 14th Amendment protections, students from immigrant families say the rise in ICE activity has left them living in fear.

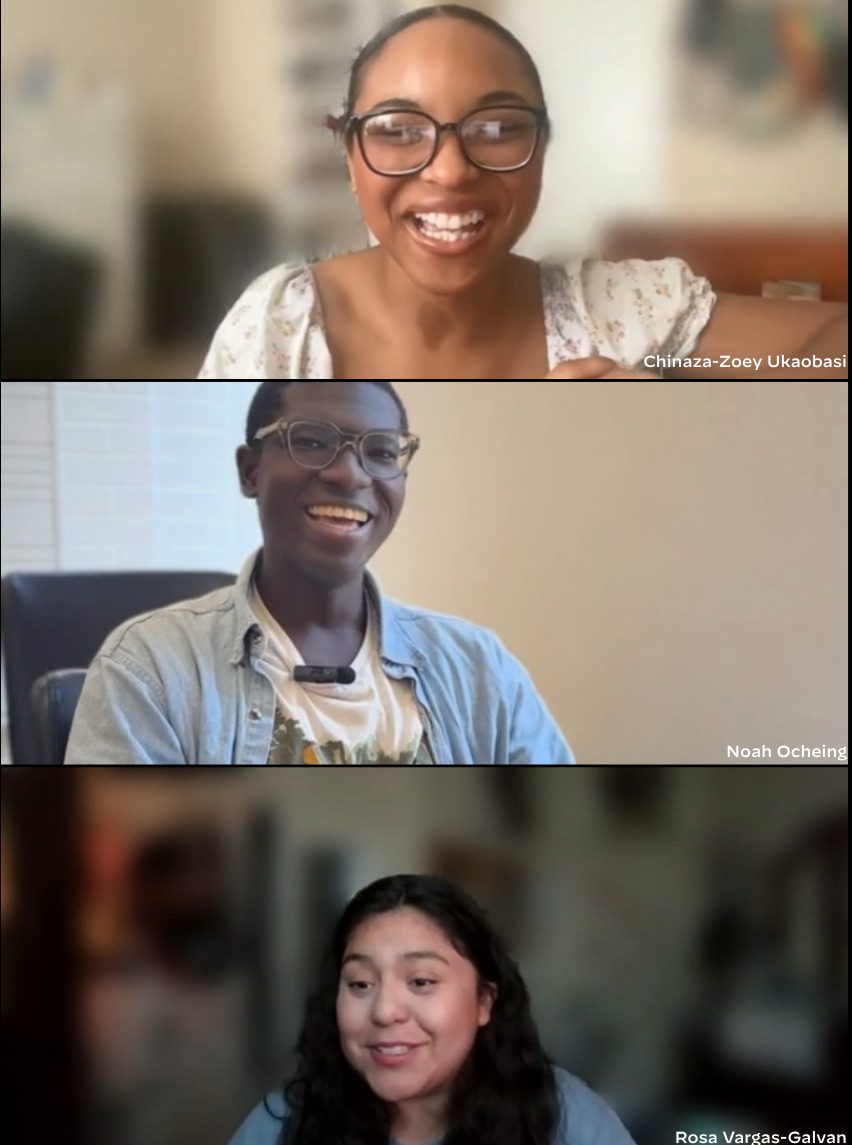

Chinaza-Zoey Ukaobasi was born in Chicago and moved to Houston when she was just two-and-a-half years old. Her parents immigrated to the US from Nigeria, and her mother utilized an educational visa while her father received a work visa.

Eventually, they became naturalized American citizens, and both of her parents worked incredibly hard, around the clock, to provide a stable life for Ukaobasi. Thanks to their sacrifices, she attends college and pursues her degree comfortably.

In recent months, however, Ukaobaisi said she and her mother have had six different people threaten to call US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on them, despite the fact that they are American citizens protected under the 14th Amendment.

“My mom has been here for 20 years,” Ukaobaisi told COURIER DFW. “She’s done nothing but work her butt off. She’s provided to this economy, she has no criminal record, and she’s been dealt the worst hand by this country.”

Since President Donald Trump came into office and began his aggressive campaign to deport unauthorized immigrants (including those without a criminal record) and dismantle birthright citizenship, college students from immigrant families like Ukaobaisi are finding themselves wondering if they can continue their education safely.

Through executive orders, the cooperation of local law enforcement, and hateful rhetoric, the federal government increased daily arrests by 268% in June this year compared to 2024, according to an analysis by The Guardian. Increasingly emboldened, ICE agents are now allowed to detain people in churches, workplaces, and schools, and critics say the lack of due process is undermining our country’s democratic values.

Citizenship doesn’t erase the fear of deportation

Rosa Vargas-Galvan is a junior at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) studying communications technology. She has been a US citizen since 2022. Before that, she was a legal permanent resident.

Before she was naturalized, Vargas-Galvan’s parents were adamant that she avoid any public activity that might draw the attention of law enforcement.

“That could have affected my residency,” she said, adding, “and [law enforcement] could have used [it] as a reason enough to send me back home [to Mexico].”

Even now, as an American citizen, Vargas-Galvan still worries she may be removed from her home in Arlington because of her complexion and race. It’s a fear that is shared by many Latino and Hispanic Americans in communities where ICE has escalated its presence.

“They’re coming after the Latino population just because they can,” Vargas-Galvan said.

This fear exists despite one of the most fundamental protections of the US Constitution: the 14th Amendment. Ratified in 1868, after the Civil War, the amendment granted citizenship to formerly enslaved people and established that anyone born on American soil is a US citizen, regardless of their parents’ immigration status.

In practice, however, those protections are not always honored. ICE raids have been conducted without first verifying a person’s legal status, and agents sometimes target people based on racial profiling. According to the Economic Times, US citizens have been wrongfully detained and even deported “due to misidentification, while others stem from flawed databases or outdated records.” The report also states that ICE lacks a reliable system to verify citizenship before carrying out enforcement actions.

In fact, data compiled by TRAC shows that 71% of detainees do not have any criminal convictions. Texas leads the nation with the most ICE detainees in fiscal year 2025.

From top to bottom, students Chinaza-Zoey Ukaobasi, Noah Ocheing, and Rosa Vargas-Galvan (Zahiyah Carter/ COURIER DFW)

The ripple effects of these decisions

At Southern Methodist University, Noah Ocheing, an American citizen whose parents have dual citizenship for Kenya and the US, is grappling with what these federal changes may mean for him and his family.

Ocheing is an incoming junior studying music education. He was born in the US after his parents entered the lottery system and won a chance to apply for permanent residence and a green card. He explains that part of his parents’ reasoning for leaving their home country was to ensure their children’s academic success.

“A huge reason they came to the US—they wanted me and my siblings to have a better shot at education here in the states.”

Along with worrying he could be blocked from re-entering the country if he ever visits family abroad, one of Ocheing’s biggest fears is that he won’t be able to finish school because of recent actions by the Trump administration. With the move to dismantle the US Department of Education and new provisions in Trump’s new tax law that affect financial aid, he’s concerned about losing the resources he needs to help pay for college.

Ocheing wants to become a music teacher, and he is wary of the fact that he may also not have the tools necessary to protect his future students as Trump’s policies continue to negatively affect every facet of education and immigration.

“I’m super passionate about that because I know that my future classrooms will have so many different people from so many different backgrounds, and if my students come in and don’t even feel like they have a place and a space that this country wasn’t for them,” he said. “How am I supposed to give them hope whenever we’re cutting out things that we’ve thought to be crucial to the American spirit?”