Gillian Grace (far right) rides at a Hurricane Katrina fundraiser in Houston. (Courtesy Gillian Grace)

When cooking a New Orleans staple like gumbo, the first step is to make the roux, a process that requires the cook to meticulously stir a combination of flour and fat. The kitchen becomes hot and steamy as the mixture begins to boil, a savory and earthy scent setting the tone for a perfect stew. If you burn it, you can forget about it. You can’t make good gumbo on a bad roux.

For many, the process signals the first day of fall, but for Gillian Grace, it reminds her of the home she lost.

Grace only called New Orleans home until she was 6 years old, before she and her family were forced to evacuate days before Hurricane Katrina blew through the city, broke several levies, and left most of the city under water.

The canal behind Grace’s house in New Orleans. (Courtesy Gillian Grace)

Though she now lives in Houston, her family originally evacuated to Memphis—there weren’t enough hotel rooms available in closer cities.

“ I remember being really excited because we were going to go to Elvis’s house, and I had a very weird obsession with Elvis,” Grace said. “ We still to this day have a picture of all of us at Elvis’s house in just shorts and t-shirts that we threw in a bag.”

Nearly 1,600 people from New Orleans died because of Katrina, making it one of the deadliest hurricanes to ever hit the US in more than 50 years, and causing $108 billion in damages. The impact can still be felt to this day: In 2005, 14,000 people called the Lower Ninth Ward, one of the hardest hit neighborhoods, home; today, that number is about 5,000.

Around 250,000 people evacuated to Houston from New Orleans, and an estimated 100,000 chose to make the city their permanent home. In honor of the 20th anniversary of this devastating storm, we spoke to three survivors about their experiences then and the lasting impact of having lived through Katrina.

A week like any other

In the weeks leading up to the storm, not many people were concerned, thinking it would pass in a few days and that the impact would be minimal. The summer season was just starting to wind down, and kids were excited for the start of a new school year.

Approaching eighth grade, Ebony Hollins had just had what she called the best summer of her life.

“ I remember every Saturday [that summer], me and my friends going to the skating rink,” she said. “ I remember my mom would let us walk to the library, or we could ride our bikes to the park It was a very tight-knit [community] and if something were to happen, [elders] would talk to our parents or our grandparents about it.”

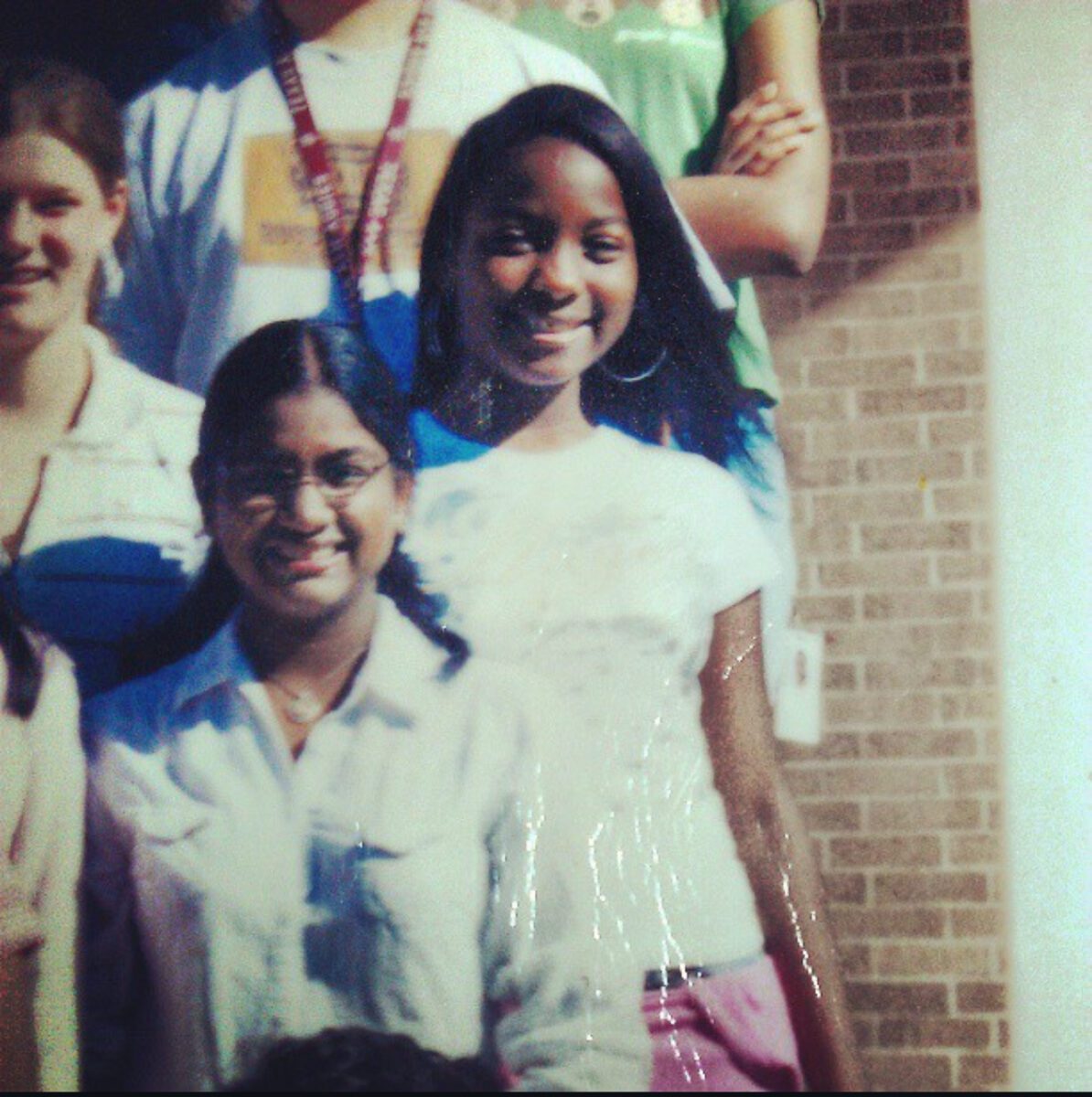

“This was my school picture my first year going to school in Houston,” Hollins said. “I remember skipping the last day of school field trip to go to New Orleans to be with my friends that I had went to school with since the second grade. Houston still felt like a foreign land and not home.” (Courtesy Ebony Hollins)

Born in New Orleans, she was excited to graduate that year, something that was seen as the pinnacle at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic School.

While some members of her family weren’t worried about the approaching storm, recalling that past hurricanes had only caused minor damage, Hollins’ grandmother thought differently. Having lived through 1969’s Hurricane Camille, she refused to take any chances. By Wednesday, she was making plans to evacuate her family, keeping the news on constantly as she prepared.

Meanwhile, Christine Collins, who was 23 when Katrina hit, thought the storm would be like any other one before.

“ Usually for people in New Orleans, when you say a storm is coming, that means start cooking everything in your freezer,” Collins said. “We’re sitting out on the porch. We’re chatting up with the neighbors and talking about our plans on who’s evacuating, whose houses we need to look out for when they’re gone, and things of that nature.”

Two days before the storm, Collins, a Navy veteran and a nurse, headed to her shift at West Jefferson Medical Center like it was any other day. By the time the severity of the storm was evident to Collins, she was already knee-deep in the work, ready to help.

She’d be away from her husband and child, though. They had evacuated toward Baton Rouge, hit traffic, and unknowingly turned into the storm’s path.

“Once the hospital lost power, I think I lost it,” Collins said. ”I’m trying to take care of patients, but I’m also trying to keep in constant communication with my family.”

Collins thought she was prepared for anything. But once her nursing duties turned to grabbing corpses off the hospital roof, she grasped the true severity of Katrina’s wrath. She remembers standing at one of the hospital windows to see the storm for herself.

“Most people were trying to hide and hunker down. I wanted to get near a window because if I’m gonna go, I wanna know what took me out,” she said.

“ I’m literally standing at the window watching tar from people’s roofs fly past, and the top of the Shell gas station fly past the window. These are things that live rent free in my head.”

Stepping into a war zone

Since Collins lived only a few minutes away from the hospital, she went back to check on her house to see the damage as soon as she was able to get away.

“ I get out of my car, I walk down the sidewalk trying to be mindful of power lines, not to step on a live wire or anything,” Collins said. “I get to my house and it’s the National Guard walking down every street with machine guns like they were literally in a war zone.”

Grace’s family experienced similar hostility, as did many others trying to return to their homes in the aftermath. Two civilians were shot and killed by New Orleans police, while four more were injured as they tried to find food and medicine. Police were reportedly aggressive with homeowners, threatening them with rifles and forcing them to show multiple forms of identification.

The plague that was hung outside Grace’s house in New Orleans. (Courtesy Gillian Grace)

“ My parents were held at gunpoint by the police because they thought they were looters and no one was allowed in the city,” Grace said. “They had to show the deed to the house, and could only grab a couple of things.”

Reuniting in Texas

For Grace’s family, the decision to move on from their temporary stop in Memphis came quickly when her aunt called about two open spots at a Houston school. Grace’s mother decided to move the whole family there.

Houston meant safety for Collins too—but only after a harrowing week. She had stayed behind in New Orleans working as a first responder, then packed up what was left of her home while she waited for her sister to arrive from Houston.

“ When my sister finally made it from Houston to get me, I got in the car, and I want to say that what might have been normally a five or six hour drive, took us 10 hours, and I slept the entire way,” Collins said. “It was just one of those things where every time you revisit that, you think about how blessed you are.”

Still, Collins couldn’t stop worrying about her husband and son, who were still missing. The shelter they had originally gone to was no longer standing.

“ You could not tell me my child and my husband were not in that water,” Collins said. “This is probably the worst imaginable thing that could happen to anybody. It felt like I had a hole in my chest.”

Eventually, she found out that they had made it to Biloxi, Mississippi, and was able to reunite with them in Houston.

Meanwhile, Hollins’ family split up in their evacuation: Her mother’s side went to Georgia while her father’s side ended up in Houston. Going back to their New Orleans home was out of the question.

Hollins (right) with her best friend since second grade, visiting friends and family in summer 2006. (Courtesy Ebony Hollins)

“ They walked into the house and that’s when they came back and they were letting us know that the entire first floor was just devastated,” Hollins said. “The second floor didn’t get hit with water, but there was mold coming up the walls.”

Being apart was hard for such a close-knit family. Hollins recalled pleading with her mom to move to Texas so they could all be together. By Thanksgiving of 2005, Hollins’ mother finally decided to take the family to Houston, where they have been ever since.

How a survivor weathers the storms

Years have passed since that devastating storm forced these three women to leave New Orleans, but they’ve adjusted to a new life in a different city. Years later, however, an all too familiar challenge came.

Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Southeast Texas on Aug. 25, 2017. For many, the storm brought back memories of Katrina.

Collins was working as a nurse in a Houston hospital, but felt it was important to be with her family during Harvey.

“ I was working at Memorial Hermann Southwest and they were like, okay, we have enough help. If you wanna leave, now’s a good time before the weather gets bad,” Collins said. “I got on 59. I shot over to the Westpark Tollway to get home. I got home and I took a deep breath and I looked at my children and I was just like, not again.”

For Hollins, the storm stirred up feelings of abandonment and loss.

“It just brought up being separated from my friends and not really getting to say goodbye because none of us really knew what was happening,” she said.

And while Harvey did not bring the same level of destruction as Katrina, it was still Houston’s worst hurricane, claiming 103 lives and causing $120 billion in damages.

While trauma lingers from natural disasters, it doesn’t necessarily drive people away from the cities they love. In fact, about two-thirds of New Orleans residents returned within a year of Katrina. Organizations like Habitat for Humanity and Operation USA have been helping survivors rebuild, relying on donations from people all over the country.

What has remained in the years since is a sustaining pride and joy in the city that so many people called home, a place that many describe as tight-knit.

And that energy is held by Katrina babies throughout the US—the location doesn’t change the spirit.

“ A lot of good people come out of New Orleans and just about all of us have a good personality,” Collins said. “We’re very kindhearted people. We’re very giving people. We’re very loving people, regardless of what people look like and who they are. We share kindness no matter what.”