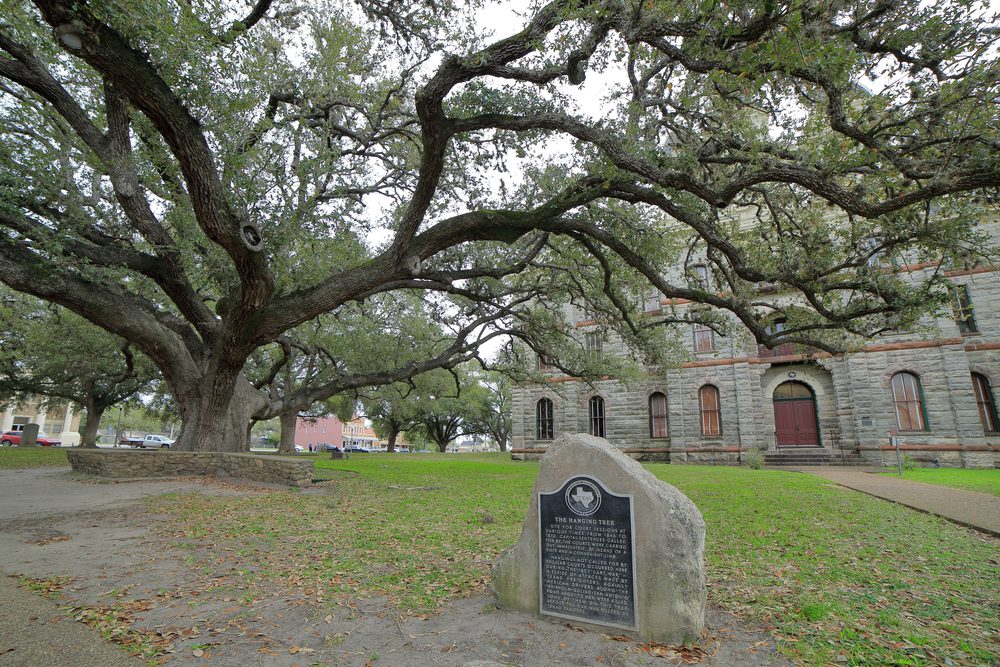

A live oak tree known as The Hanging Tree sits in front of the Goliad County courthouse with a historical marker in Goliad, Texas. (JustPixs/ Shutterstock)

Texans like to talk about the parts of its history that make us look big and bold: a thriving oil industry, leadership in cattle rearing, and historic space exploration. But there’s another history just as big as the parts we love to celebrate—something far more shameful—the era when racial terror lynchings were not only tolerated, but celebrated, in communities across our state. And those murders are still being downplayed today.

The Equal Justice Initiative has to date documented over 4,400 racial terror lynchings throughout the South between 1877 and 1950. That’s more than one a week for 73 years. Lynching In Texas’ (A project I worked on as a fact-checker at Sam Houston State University) database contains more than 600 lynchings. The deadliest year in the US was 1892, when 230 people were lynched nationwide, about one every other day. Many of those killings took place in Texas. And according to the Lynching In Texas project, more than just a few happened around the greater Houston area.

Consider the lynching of 21 year old Oscar Beasley in Angleton, Texas, on September 17, 1920. According to The Galveston Daily News, Sheriff John Snow arrived at Beasley’s home with a warrant for saddle theft. The paper claimed Beasley shot and killed the sheriff on the spot, then fled. By the next morning, he was captured in nearby Danbury and brought back to Angleton.

That’s the official story. But that leaves out a crucial note in history: Southern newspapers in this era often omitted crucial facts, inflated accusations, and published the accounts of people who had, themselves, taken part in the lynching. Even decades later, editors like those at the Montgomery Advertiser would admit to this bias, acknowledging that victims were “characterized as guilty before proved so” and that newspapers “often assumed they committed the crime.”

No matter the truth behind the killing, Beasley never had a real chance at trial. The following day a grand jury indicted him with murder and later that afternoon, The Galveston Daily News reported, “several hundred men, from this and adjoining counties” gathered in Angleton to hang Beasley from a willow tree, despite the deputy sheriff trying to stop it.

White lynch mobs weren’t fringe extremists. They were the community: white workers, doctors, lawyers, business owners, even elected officials. Lynching was a public ritual, often with hundreds or thousands of spectators. Researchers Amy Kate Bailey and Stewart Tolnay describe them as “carnival-like events” where food vendors set up shop, photographers sold postcards of the corpse, and body parts were collected as souvenirs.

In Beasley’s case, a mob of over 300 men stormed the Angleton jail, overpowered Deputy Sheriff L.R. Johnson, dragged Beasley outside, placed a rope around his neck, and hanged him from a tree in the jail yard. His body was left there swinging in the tree, in plain view of anyone passing by. Angleton’s Black residents would have had no choice but to see Beasley’s body, to carry that image with them—a reminder that they could be next. And that was the point.

This was not “vigilante justice.” It was a political act. Part of a systematic effort by white society to terrorize Black communities and enforce white supremacy after the Civil War and Reconstruction. Public lynchings served as both punishment and propaganda, sending a clear message: this is a white man’s state, and Black lives will be taken with impunity.

This was the reality for Black people in the south. What the Columbia Historical Museum in Brazoria County recently referred to as “old fashioned frontier justice” was and is known to Black people as lynchings. Cross burnings. Mutilation. The museum described other Brazoria County lynching victims, Ransom O’Neal and Charles Tunstall, as men who were “dealt with,” adding that they were dealt with “without the waste of taxpayers’ dollars feeding and housing them for months…” This exact mindset fueled further lynchings.

Contrast that with the words published in 1903 by The Appeal, a Black newspaper in St. Paul, Minnesota: “We do not plead for, any clemency, for any favors whatever, to be shown toward Afro-Americans accused of crime…but we do, most vehemently, protest against the all too frequent practice which obtains in the South-and, alas, in the North too, to an alarming extent-of white men taking the law in their own hands and wantonly, inhumanly, barbarously butchering [sic] men and women just because there is a visible admixture of African blood in their veins.”

We often speak about this history as if it is long ago, but the culture that enabled it, the rush to declare Black people guilty without evidence, the willingness to excuse or ignore racially motivated violence when it’s committed by those in power, has not disappeared. Its echoes are present in the way we explain away police shootings of unarmed Black men today.

We cannot undo what happened to Oscar Beasley, but we can refuse to rewrite history to excuse it. When a museum describes his killing as “old fashioned frontier justice” or says lynching victims like Ransom O’Neal and Charles Tunstall were “dealt with” to save taxpayer money, it is repeating the propaganda of lynchers themselves. This language doesn’t simply tell history, it justifies racial terror. It places Beasley, O’Neal, and Tunstall alongside modern-day killers, erasing the reality that they were denied trials, stripped of due process, and executed by mobs.

To glorify lynching as swift justice is to side with the perpetrators. These killings were not about protecting law and order; they were about maintaining white supremacy and terrorizing Black communities. Telling this truth is not about shaming the county’s past; it is about refusing to let myths of “justice” obscure atrocities carried out in broad daylight. Anything less turns victims into villains and lynchers into heroes, perpetuating the very injustice that history should teach us to reject.