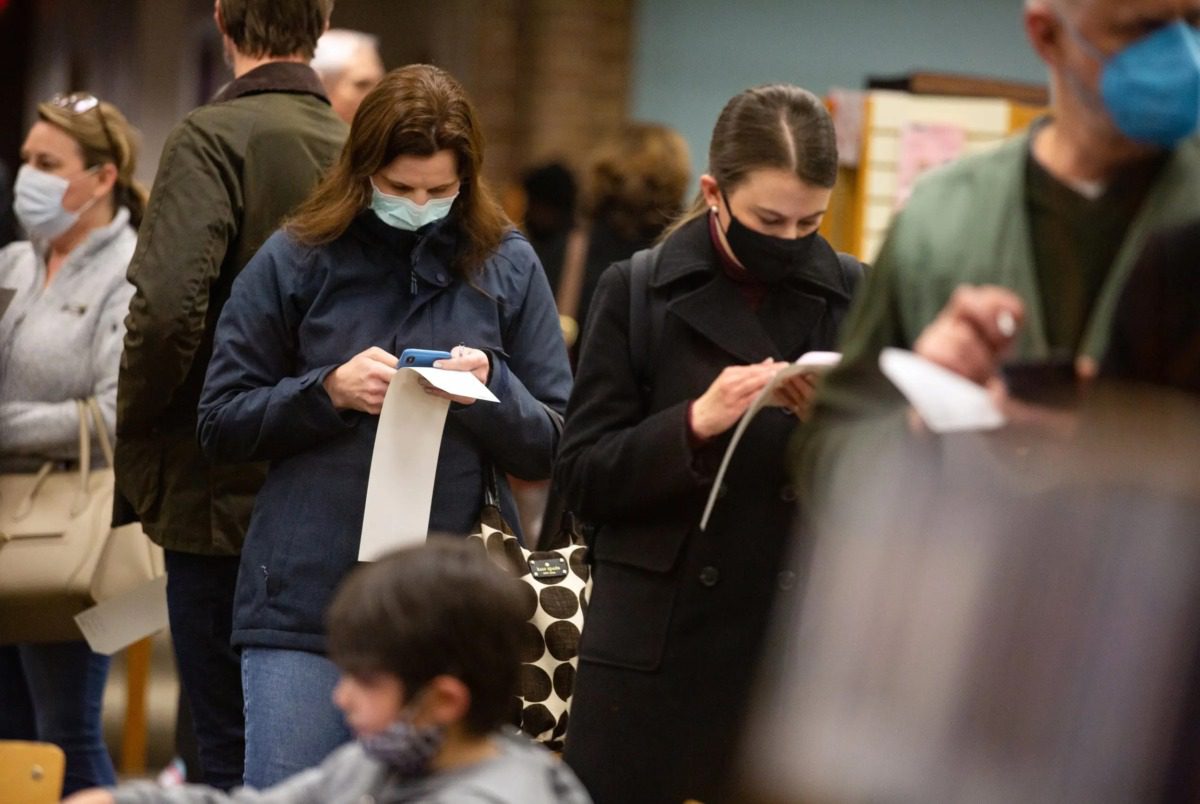

Voters wait in line at the Lakewood Branch Library in Dallas on Feb. 25, 2022, the last day of early voting in the Texas primary. Dallas County voting centers’ hours were extended till 10 P.M. on the last day of early voting to make up for early closures due to icy weather. Photo Credit: Shelby Tauber for The Texas Tribune

Disinformation spikes during major U.S. elections. Experts urge verifying sources, fact-checking and careful content sharing.

With every major U.S. election cycle, disinformation takes center stage once again, sowing confusion and eroding trust in democratic processes. This trend is far from surprising: the Global Risks Report from the World Economic Forum estimates that disinformation will be one of humanity’s greatest threats over the next two years.

Rumors and falsehoods circulating on social media, often spread by politicians and influential figures, have become a problem of unprecedented scale — nearly six new false claims about the election have emerged each week since late August, according to the Election Disinformation Tracking Center at NewsGuard.

Many of these narratives are not new. Sources of disinformation often recycle and adapt to current context unfounded claims about fraud, the integrity of mail-in voting, and other baseless narratives. To avoid misinformation, the most important thing is what it is about.

Common False Narratives: Voting Machines

In Texas, a persistent rumor suggests that electronic voting machines switch votes between Democrat and Republican candidates. In 2022, it was confirmed that this is false. While some touch screens can be challenging to use and may lead to accidental selections, officials and security experts explain that this does not indicate an intentional vote change.

Voting machines, implemented 20 years ago, have been subject to speculation regarding their accuracy and potential for manipulation. Carolyn Graves, Midland County election administrator, compared using these machines to typing a message on a small keyboard.

“If you don’t hit it with the tip of your finger, you might press one of the letters around it,” Graves said. “It’s basically the same. If you don’t press with the tip of your finger or tilt it to one side, you might hit the other [option].”

For this reason, both authorities and experts advise voters to carefully review their ballots to confirm their selections before submitting. If there is an error on a printed ballot, voters are entitled to request up to two additional ballots to make corrections. Incorrect ballots are voided and not counted.

Common false narratives: Migrants voting

Another recurring rumor in the 2024 presidential campaign suggests that undocumented immigrants are registering to vote using only a Social Security Number (SSN). This claim has been spread by politicians, influential figures like entrepreneur Elon Musk, and in Texas, a Fox News presenter mentioned this theory on air. Although debunked, it prompted an investigation by Attorney General Ken Paxton.

An account on X that disseminated this misinformation claimed that in Texas, the number of people registering to vote without a photo ID was 1,250,710. Texas Secretary of State Jane Nelson stated in a press release on April 3, that “it is completely inaccurate to claim that 1.2 million voters have registered to vote in Texas without a photo ID this year. The truth is that our voter roll has increased by 57,711 voters since the beginning of 2024. This is less than the number of people registered in the same timeframe in 2022 (about 65,000) and in 2020 (about 104,000).”

Moreover, Texas law is clear: only U.S. citizens aged 18 or older can register to vote. Citizens who have been convicted of a felony and are still serving a sentence, including probation or parole are not allowed to register to vote.

The state’s registration process involves filling out a paper form and submitting it to the county voter registrar where they reside. Texans can also register through the Texas Department of Public Safety when renewing their driver’s license or state ID. Additionally, they can register with a trained volunteer deputy voter registrar appointed by the county.

The voter registration form requires voters to verify the eligibility criteria listed on the form and sign an affidavit acknowledging that lying may result in perjury penalties.

What to do about misinformation and how to prevent it

Anyone with a cell phone can contribute to combating misinformation, and you don’t need specific fact-checking skills. The first and most important step: if you’re not sure that an informational content is true, don’t share it!

Experts like Laura Zommer, founder of the Spanish fact-checking initiative in the U.S. FactChequeado, recommend being especially cautious in the days immediately before and after elections, as misinformation tends to increase during these times. Therefore, it is essential to consider the following aspects:

* Verify sources: Before sharing information, consult reliable sources, such as established media outlets and official organizations. Make sure to identify the author of the content and check their credentials to ensure reliability.

* Be cautious with sensational content: Viral stories often use exaggerated claims to provoke strong emotions. Verify these stories with established and trustworthy news outlets.

* Use fact-checking tools: Free fact-checking tools can help you quickly assess the reliability of claims, especially on social media. Platforms like Politifact, FactCheck.org, FactChequeado, and others provide comprehensive analyses on various topics.

What to expect with the results

No national agency is charged with collecting and publishing election results. Elections are managed locally, following the standards set by each state. In Texas, this responsibility falls to the Office of the Secretary of State.

On Nov. 5, at 7 p.m., the first preliminary results, including early voting returns, will be available as soon as the polls close. However, official results will not be published until after Nov.18, once all late-arriving mail-in ballots, as well as military and overseas citizen votes, have been received and counted.

You can follow the vote count in real time on the Office of the Secretary of State’s website. In this Tribune article, we explain the vote-counting process in more detail.

Another reliable resource for obtaining accurate results is the counting conducted by the Associated Press (AP). Since 1848, AP has carried out counts of results in national, state, and local elections, which attests to its extensive experience and reach in electoral coverage. The news agency works closely with local election officials to receive results directly from the counties and districts where votes are counted. The collected information is sent to AP’s reporting center, a process that involves approximately 4,000 people.

Election results undergo thorough verification. AP’s reporting focuses on one key question: Can trailing candidates catch the leader? The race is only called when the answer is a definite “no.”

Minimal possibilities of electoral fraud

While there are documented cases of election fraud in Texas and across the United States, they are extremely rare. The Heritage Foundation recorded 103 cases in Texas between 2005 and 2022, but more than 107 million votes were cast in the state during this period. This suggests that fraudulent votes represented about 0.000096% of votes cast in 2020.

Regarding immigrant voting, the Brennan Center for Justice concluded that out of a total of 23.5 million votes cast in 42 jurisdictions during the 2016 elections, only 30 cases of possible non-citizens voting were reported for further investigation or prosecution.